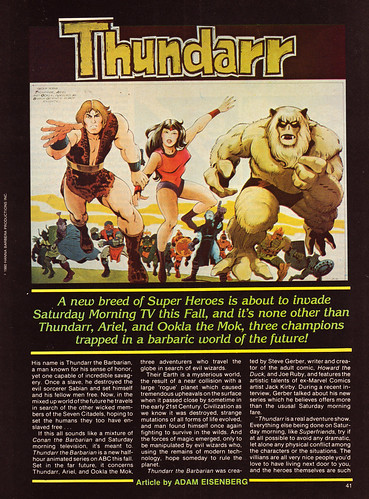

I found some time this weekend and scanned another Thundarr the Barbarian article. This one comes from an issue of Fantastic from 1980, though for the life of me I can’t remember which month. It was written by Adam Eisenberg and makes a nice companion piece to the Fangoria/Buzz Dixon article I posted before, though it centers on more of the limitations and censorship the series had to overcome because of the imposed network standards and practices…

I know I tend to go on and on about this idea time and again, but I think it’s interesting to note just how important the 1980-1983 timeframe was for modern action animation. In the piece Steve Gerber talks a little bit about the collective intentions to bring the “action” back to action/adventure cartoons while creating Thundarr with Joe Ruby (of Ruby Spears.) First off, though he was already working in animation doing production design for Hanna Barbera, Jack Kirby was probably hot on Gerber and Ruby’s minds because of what he brought to the table for Marvel and DC comics. I think it’s really cool to see an animation production team playing to the strengths of their contracted talent instead of trying to force them to bend in another direction, which doesn’t always bode well in network/studio environment.

At the same time, Gerber admits that even while shooting for the stars in terms of creating a thrilling action oriented cartoon they still had their hands tied to an extent where their barbarian hero couldn’t “…throw a punch or…even hit anybody. He can do all kids of acrobatic things, but he can’t even trip anyone.” This kind of over protective standards and practices is equal parts infuriating and incredibly flooring. Whereas it’s frustrating to watch a cartoon that centers around a barbarian that you just know wants to knock the block off of every douche-bag wizard that he runs across (they are enslaving humanity you know), these limitations opened the door to exploring another heroic archetype, the strong non-violent hero (think He-Man.) Though I know it’s really easy to bag on the He-Man ideal for being too goodie good and unrealistic, this kind of storytelling is not always about focusing on the visceral and gritty realism. Sometimes it’s about fables and though I know this is obvious, morality. This is what’s really cool about a great creative environment, that there is room to explore both paths (and more), so you can have something more fist in the face like G.I. Joe, something more moral like Masters of the Universe, and something inbetween like Thundarr.

So this short period in animation is so interesting to me because it marks the beginning of the end of 10 long years of anti-integrity self-imposed studio censorship…

Similarly Gerber and Ruby found themselves challenged by another aspect of depicting violence in cartoons in that they weren’t allowed to have any kind of traditional barbarian sword for the Thundarr character. According to S&P there could be no sharp objects like knives or swords. Though it could have hampered some of the design aesthetic on the show this limitation pushed them to create something interesting and new in Thundarr’s Sunsword. Trying to sidestep riffing too much off of Star Wars the sword was designed to have a blade forged from a bolt of lightning. Again, even though they were hampered by network S&P the crew ended up treating this as a chance to bring something relatively new to the table, or at least they used it as an opportunity to tie in a different set of influences than a barbarian fantasy cartoon would normally lean on. It’s less Conan and more Norse god in look and design. Again, this is certainly playing to the strengths of Jack Kirby who brought a taste of his work on characters such as Thor and the various 4th World creations for DC.

Here’s another Gerber quote from the article that I love…

“The big thing that we’ve had to overcome is that the censors tend to treat children as if they’re not just morons, but lunatics, potentially dangerous creatures.”